Like the people who compose them, teams have their personalities, too. Those team personalities arise from the mission or missions for which a team has responsibility for, on the one hand, and the characteristics of the members of the team.

This is a short story about two teams whose team personalities differed sharply. Both teams resided in a enterprise in the computer products industry. The Design team was responsible for creating particular computer components. The Process team took responsibility for shepherding newly introduced components through the assembly and manufacturing process.

Members of the two teams differed in their backgrounds and experience. Membership in the Design team mainly consisted of electrical engineers and IT specialists, whereas Process team members mostly were manufacturing and industrial engineers, albeit with computer industry experience.

The mission for the Design team was to conceive of and create designs for innovative and efficient components. The mission of the Process team was to see to it that new components would assure that the production of new components followed a “high-yield” process – lots of components produced efficiently with minimum errors and production rejects.

In working with the Design and Process team we assessed the 10-12 most senior members of each of the teams. The assessment focused mainly on styles of thinking and deciding. Briefly, the assessment generated team member profiles that characterized members’ modes of thinking in terms of speed, analytic thinking, and outcome focus. The chart shown in Table 1 below describes the four styles of thinking and deciding that were measured.

As the table shows, the two styles on the left are action-oriented; the two on the right are more thinking-oriented. The two on the top are “uni-focused,” inclined to focus on achieving one particular outcome or goal at a time. The bottom two are “multi-focused,” aiming at achieving multiple goals or outcomes. The uni-focused styles, Decisive and Hierarchic, tend to stick to a straight course of action to achieve a special goal. The multi-focused styles, Flexible and Integrative follow multiple courses of action to achieve multiple outcomes, not just one. Most people have a primary and secondary style that they use more often than the other styles.

Those courses of action also can shift and change.

These styles describe ways of thinking and decision-making that can differ markedly. For example, when working in the Decisive mode, decisions are made swiftly based on just a few key facts. Decisions made tend to be final. So, fast and focused is the theme of the Decisive style. However, when in the Integrative mode, a lot of information is taken in and considered before a decision is reached, and then the inclination is to look for a strategy that achieves a number of different objectives, not just one. Consequently, speed is replaced by analysis, which takes time. A very focused path is replaced by a strategy calling for plans of attack and actions that might be modified and adjusted as things evolve. In this mode, decisions are processes, not events. Thoroughness and broad adaptive strategies are the theme now. No decision is absolutely final.

The other two styles differ markedly also. The Flexible style is an action-oriented style in which decisions are made swiftly but remain subject to quick change and shifts in direction, just a quickly. The Hierarchic styles is a highly analytic and logic-driven style involving a search for the single best plan or strategy. Once a decision is made carefully, a straight and narrow path is pursued until the intended objective is achieved.

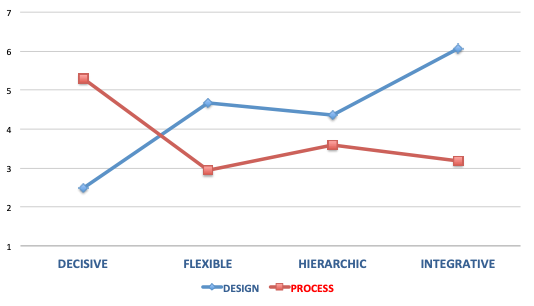

Back to our tale of two teams. Figure 1 shows the average scores of Design team members on the four styles. As the profile shows, the style of thinking that stands out most prominently, is the analytic, multi-focused, Integrative style. The more action-oriented, but nonetheless, multi-focused Flexible style shows up as a secondary theme. And, the action-oriented, and uni-focused style takes fourth place. Clearly, this is a thinking-oriented and exploratory team who has in mind many goals and outcomes. The profile indicates that the team will take its time and look at quite a few options before deciding and formulating a plan and strategy. This profile appears to be a good fit with the team’s charter: designing new components.

Figure 2 shows average scores of Process team members. In this case, the primary style is the fast, action-oriented and uni-focused, Decisive style with the analytic and uni-focused Hierarchic style as secondary. This profile describes a team very focused on getting things done, achieving a high level of productivity, efficiently (but without compromising quality, given the Hierarchic secondary style), and consistently pursuing a particular course of action. The profile appears to be a good fit with the Process team’s mission to actually efficiently produce a high yield of component devices.

So, the indications are that the two teams are set up well with the mindsets necessary to execute their missions. All observers agreed that the teams each performed well.

Nonetheless, things did not work so well in the interface between the teams when they interacted, as they needed to do. The Process team needed to plan ahead for components in the design platform and the Design team needed to create components that would not only work as intended but that actually could be produced effectively and inexpensively. This all required interaction. And, that’s when things become difficult.

At a glance, Figure 3 presents shows the profile graphs for the two teams superimposed over each other. One does not need to be an expert on styles of thinking and decision-making to see from the graphs that communication and mutual decision-making would be difficult. In terms of thinking and deciding, the graphs differ sharply and show two distinctly different mindsets! They are virtually opposites! The graphs basically depict two very different mindsets.

Although, each team seemed well-composed for its respective mission, trouble arose in the interface between the teams. The did need to interact and coordinate. But, their views on issues differed sharply. When we met with members of each team, we heard plenty of griping about the other team.

Design Team Complaints

From the Design team’s perspective, their colleagues on the Process team were anything but cooperative. They wanted everything done right now! They had no tolerance for any delays. Changes to schedules brought loud complaints and arguments. The Process team members, we were told, were downright resistant and obstructive. Senior managers responsible for the teams frequently were called upon to resolve disputes. There were many bruised feelings. Negative images of members of the Process team had become very deep-seated.

Design team members pointed out that they were responsible for creating new, innovative components with improved performance capabilities. Accordingly, they pointed out, that meant that changes were necessary and inevitable. Moreover, they said, the fact that they were supposed to be creating new and improved components that did not already exist assured that things would change. Why couldn’t Process team members understand and appreciate these simple facts, they wondered.

From the Process team’s perspective, the Design team members seemed oblivious to the fact that the components they designed actually had to be manufactured. That simple fact imposed constraints on designs. Even a seemingly simple tweak to a design could require a non-simple change to the manufacturing process. So, any changed should be vetted carefully before becoming part of the new design. Moreover, the absolute number of changes should be controlled carefully to minimize disruptive new manufacturing requirements. But, from the point of view of the Process team members, these considerations seemed to mean nothing to the Design team. To make matters worse, changes not infrequently were made to the changes themselves. A new design would be proposed. The Process team would try to get a head start by making manufacturing adjustments. But, then, the proposed change would be altered and whatever adjustments had been made had to be abandoned or altered again. All of this required time and resources. Inevitably, unanticipated glitches would pop up in production processes and yields would suffer – a very negative outcome for the Process team who were expected to keep yields high. “Why can’t, or won’t, the Design team members just be reasonable and considerate, instead of creating chaos and waste?” they wondered.

You might have noticed that these perceptions, on the part of both teams, that there were some important gaps. Most notably, neither team seemed to appreciate that the other team was behaving responsibly in terms of the team’s charter. The Design never commented on the fact that design changes that complicated the production process and could compromise production yield actually were in direct conflict with the Process team’s performance objectives and compromised the team’s effectiveness. By the same token, the Process team never acknowledged that creating innovative new components was exactly what the Design team was supposed to do and necessarily resulted in design changes that might require different production setups. Each team seemed riveted on its own performance objectives with minimal, if any reflection on the fact that the other team had responsibilities very different from its own.

Even more elusive, was the fact that the members of each team possessed a mindset very well suited to the team’s mission and very different from the mindset of its own members. They didn’t realize that the each need to think in ways quite different from their own team’s way of thinking. Instead, as so often is the case, they implicitly assumed the other team’s way of thinking and behaving was wrong. Things were either right or wrong, and the other team was wrong!